|

| Narendra Modi speaks on the occasion of Bangladesh's 50th Independence Day - FOCUS BANGLA |

SALEEM SAMAD

Fifty years ago, in 1971, India added colours of victories and feathers on Bangladesh’s hat.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently came, saw, but couldn’t conquer the hearts and minds of the people of Bangladesh. His Bangladesh visit was to mark the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh’s nationhood, despite the coronavirus pandemic.

Possibly, Modi couldn’t fulfil the expectations of the “aam janata” of the country.

The agitation spearheaded by the left alliance and its student group protested Modi’s visit. Quickly, the Islamist groups voiced their protests, followed by the rightist parties.

The Islamists blamed India for the persecution of the Muslims in India, especially in Kashmir.

None was surprised as to why the Islamists, right and left elements, failed also to mention the Uighur Muslims facing ethnic cleansing in China, the crimes against humanity in Balochistan under Pakistan occupation, and the humanitarian crisis in Yemen caused by the proxy war by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against Iran.

Nothing to deny about the fact that the two South Asian neighbours, Bangladesh and India, share a common history, and linguistic and cultural heritage. The two neighbours’ strategic locations complement each other and offer an opportunity to further develop economic ties.

Nevertheless, the brutal birth of Bangladesh shattered the so-called myth of the contentious “two-nation theory,” a dream of the founder of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, in less than 25 years.

East Bengal, a Muslim majority region, decided to be wedded into weird bondage with a country separated by nearly 2,026 kilometres. But elites and military rulers of Pakistan frowned at the fish-and-rice-eating Bangalis as second-class citizens.

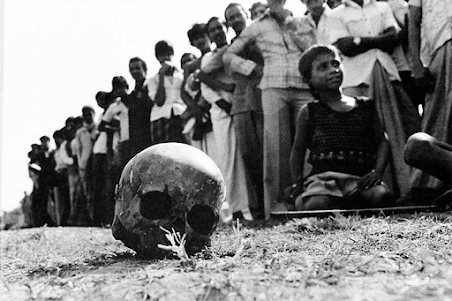

After nine months of birth pangs, the country was liberated from the yoke of the marauding Pakistan troops.

India is the world’s largest democracy, but it was not economically stable in the 70s, and had to bear the burden of providing shelter, food, and health care to more than 10 million refugees.

As the war unfolded in the eastern theatre, India embraced new enemies, including China, the United States, and the Arab countries, as she stood shoulder to shoulder with Bangladesh.

The good offices of Indian civil administration, diplomacy, and armed forces played a pro-active role in creating a nation.

The military and diplomacy of the countries mentioned above tilted towards Pakistan, which further encouraged their evil plans to commit genocide, with the intent towards ethnic cleansing of Bangalis as a nation.

The military hawks in Rawalpindi GHQ deliberately targeted Hindus after declaring them as Kufrs or Kafirs -- enemies of Islam.

To augment military aid to the Liberation War, to muster support from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, India signed the historic Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Cooperation on August 9, 1971.

The Indo-Soviet treaty had a direct impact on the decisive battle, which expedited Bangladesh independence and brought about the surrender of occupation Pakistan forces in mid-December 1971.

Indira’s efforts in September to win the hearts of the West and international bodies in favour of the Bangladesh cause had indeed melted the ice.

Months after the war, a joint communiqué surprised many that the two countries (Bangladesh and India) had agreed to pull out the victorious Indian army. Never in military history has a victorious army withdrawn so quickly.

It was hailed as the first diplomatic success by the independent hero Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangabandhu.

Yet another request by Sheikh Mujib to shift the 93,000 prisoners of war (POW) of Pakistan armed forces and civilians to India was also agreed upon.

For a justifiable relationship of the newly emerged nation, a controversial Bangladesh-India Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Peace for 25 years was signed between visiting Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her counterpart Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on March 19, 1972. The treaty, however, was bitterly criticized by the opposition, stating it as a treaty of the hegemony of India.

Well, the relations between the two neighbours were on rough seas. The border killings of Bangladesh nationals by the Indian Border Security Force (BSF), water-sharing of the Teesta rivers, and tilted trade imbalance remained major bottlenecks to the improvement of the relationship.

Besides issues of shared interests between two counties, Modi offered prayers at two temples in Satkhira and Gopalganj, which evoked curiosity in both Bangladesh and India.

His visits to Hindu temples is likely to pay dividends to influence elections in West Bengal. Meanwhile, violence raged in Brahmanbaria for the third consecutive day, leaving 12 dead, including in Chittagong and Narayanganj.

First published in the Dhaka Tribune, 31 March 2021

Saleem Samad, is an independent journalist, media rights defender, and recipient of Ashoka Fellowship and Hellman-Hammett Award. He can be reached at saleemsamad@hotmail.com. Twitter @saleemsamad