SALEEM SAMAD

In a crucial meeting held in Washington DC, on the morning of December 6, 1971, was attended by senior officials of departments of State, Defence, Joint Chief of Staffs, CIA, USAID, and others.

The heavyweight US Secretary for State at the onset of the meeting asked Gen. Westmoreland: What is your military assessment? How long can Pakistan hold out in the east [Bangladesh]?

Gen. Westmoreland candidly said, up to three weeks. Once Pakistan Army runs out of supplies, all the troops in East Pakistan [Bangladesh] will become a hostage.

No doubt sly Kissinger was worried about the safety and security of marauding Pakistan’s troops battling in occupied Bangladesh.

The United States seriously wanted to stick with withdrawal and ceasefire not a humiliating surrender of Pakistan troops and Kissinger assured the Pakistan regime that they doing all the best they can do diplomatically.

The perturbed Kissinger believed that there would be a massacre of the disarmed troops in the hands of the Mukti Bahini (Bangladesh Liberation Forces) after enemy soldiers are disarmed.

Three days after a full-scale war between India-Pakistan on the eastern front and Bangladesh-India jointly against Pakistan in the eastern war theatre, Henry Kissinger asked how long Pakistan troops can hold in Bangladesh.

The officials discussed whether there were any possibilities of Pakistan troop evacuation. Gen. Westmoreland responded in negative.

A senior official of the State Department asked Gen. Westmoreland that assuming the Indians take over Bangladesh, how do you think it will happen.

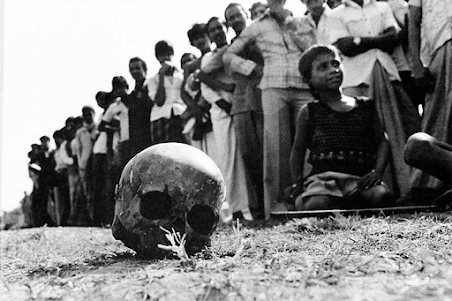

Gen. Westmoreland: I think their primary thrust will be to cut off the seaport of Chittagong. This will virtually cut off any possibility of resupply. Then they will move to destroy Pakistan’s regular forces, in cooperation with the Mukti Bahini. They will then be faced with the major job of restoring some order to the country. I think there will be a revenge massacre — possibly the greatest in the twentieth century.

Kissinger asked shall the Indians withdraw their army once the Pakistan forces were disarmed.

Gen. Westmoreland replied that he thinks they [Indians] will leave three or four divisions to work with the Mukti Bahini and pull the remainder back to the West [Pakistan].

The officials expect that the Indians will pull out as quickly as they can. Once the Pakistan forces are disarmed, the Indians will have a friendly population. They can afford to move back to the border areas quickly.

Another official in the nerve-breaking meeting predicted that after the Indian Army has been in Bangladesh for two or three weeks, they will be accepted as a “Hindu army of occupation”.

Kissinger asked: What will India do with Bangladesh? Will they see it as an independent state or have them negotiate with Islamabad?

An official responded that India has already recognised Bangladesh as an independent country. Kissinger said then there is no hope for Pakistan to negotiate with Bangladesh.

The objective of the prudent Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government was to force a surrender of the Pakistani troops in Bangladesh within 10 days.

In a telegram from New Delhi on December 6, US Ambassador Kenneth Barnard Keating reported that Indian Foreign Secretary Triloki Nath Kaul had expressed “disappointment, shock and surprise” that the United States had tabled the resolution it did in the UNSC.

On December 5 the Soviet representative on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) vetoed an eight-power draft resolution that called for a ceasefire and mutual withdrawal of forces, as well as intensified efforts to create the conditions necessary for the return of refugees to their homes.

However, the UN Security Council accepted on December 6 that an impasse had been reached in its deliberations on the conflict in South Asia, and referred the issue to the General Assembly adopted by a vote of 11 to 0 with 4 abstentions.

On the other hand, Pakistan’s General Yahya Khan’s administration conveyed their intentions to retreat from their eastern wing to the United Nations on 10 December 1971, and a formal surrender was submitted and accepted when the Commander of Eastern Command and Governor of East Pakistan, General Niazi, signed an instrument of surrender with his counterpart, Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, Commander of Eastern Command.

An estimated 93,000 Pakistan troops and civilians including family members made an unconditional public surrender in Dhaka on December 16, 1971, which is observed each year as Victory Day both in Bangladesh and by Indian armed forces.

The surrender was indeed the largest surrender that the world had witnessed since the end of the Second World War.

Conclusion: Despite the growing anger among the Mukti Bahini commanders to avenge the extreme barbarity unleashed by Pakistan troops, fortunately, none of the disarmed enemy troops was killed or died for being held captive in military garrisons inside Bangladesh.

Soon after the Prisoners of War (POWs) were transferred to India, as newly born Bangladesh did not have the ability to the containment of such a huge number of POWs.

Under Tripartite Agreement in April 1974 between Bangladesh, India and Pakistan signed in New Delhi enabled the repatriation of all the 79,676 uniformed POWs and 13,324 civilians to Pakistan, including the 195 officers held for suspected war crimes.

First published in The News Times, December 16, 2022

Saleem Samad, is an independent journalist, media rights defender, recipient of Ashoka Fellowship and Hellman-Hammett Award. He could be reached at <saleemsamad@hotmail.com>; Twitter @saleemsamad