Judge Hamoodur Rahman, along with two Pakistan High Court judges, worked tediously for five years and was able to submit the final reports on the Pakistan military’s failure since they launched the notorious “Operation Searchlight.”

However, the report lies buried, with little or no accountability; the report never saw the light of day and was kept as highly classified documents in fear of backlash.

The Hamoodur Rahman Commission (also known as the War Enquiry Commission), assessed Pakistan’s military involvement from 1947 to 1971. The commission was set up on December 26, 1971.

When the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army threw their full might, the occupation forces had to negotiate an instrument of surrender on December 16, 1971. The surrender at Dhaka, according to war historians, was the largest surrender of the military after the historic surrender of Germany, Italy, and Japan, which brought an end to WWII.

The Commission interviewed 213 persons of interest that included former president Yahya Khan, politician Nurul Amin, Abdul Hamid Khan (Chief of Army), Abdul Rahim Khan (Chief of Air Force), Muzaffar Hassan (Chief of Navy), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, senior commanders, activists, journalists, and various political leaders.

The Commission also interviewed Gen Tikka Khan, Gen AAK Niazi, and Gen Rao Farman Ali who were responsible for the horrific war crimes in Bangladesh.

In 1974, the Commission again resumed its work and interviewed 300 freed POWs and recorded 73 more bureaucrats’ testimonies that served on government assignments in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

The report recognized the atrocities and systematic massacre at Dhaka University which led to recommendations of holding public trials for civilian bureaucrats and court-martials for the senior officers. It is theorized that the first report is very critical of the Pakistan military’s interference in politics and misconduct of politicians in the country’s political atmosphere.

The military headquarters in Rawalpindi and Bhutto himself maintained that the first report should be classified to “save [the military’s] honour”. The report was marked Top Secret because Bhutto told Indian journalist Salil Tripathi in 1976 that he was concerned that it would demoralize the military and might trigger unrest.

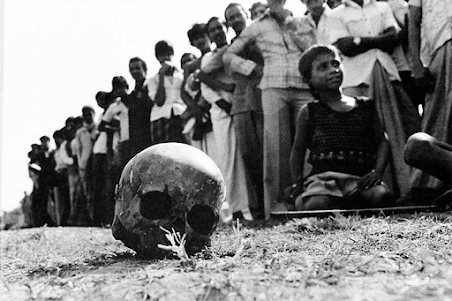

Both the first and the supplementary report lashed out at the Pakistan Army for “senseless and wanton arson, killings in the countryside, killing of intellectuals and professionals and burying them in mass graves, killing of officers of East Pakistan Army and soldiers on the pretense of quelling their rebellion, killing East Pakistani civilian officers, businessmen and industrialists, raping a large number of East Pakistani women as a deliberate act of revenge, retaliation and torture, and deliberate killing of members of the Hindu minority.”

The report also did not hesitate to accuse military dictator General Yahya Khan of being a womanizer, debaucher, and an alcoholic. He was forced to step down after Pakistan’s defeat in December 1971.

Rahman asked Bhutto for the feedback and status of the report. Bhutto remained silent for a while and replied that the report was missing. It was either lost, or stolen, and was nowhere to be found, he remarked.

Justice Rahman also asked the Chief of Army Staff General Zia-ul-Haq on the fate of the report who also commented that the original report was nowhere to be found, and nobody knew where the report went missing -- either at the Army GHQ or the National Archives of Pakistan.

In the 1990s, curiosity over the report grew when a Pakistan daily newspaper leaked the classified report which was lying at the army HQ in Rawalpindi.

The trials of Gul Hassan, Abdul Rahim Khan, and Muzaffar Hassan were held in the light of the Hamoodur Rahman Commission’s recommendations.

In December 2000, 29 years after the report was compiled, the War Report was finally declassified by Pakistan’s military dictator Pervez Musharraf. Subsequently, Bangladesh officially requested a copy of the report through diplomatic channels.

First published in the Dhaka Tribune on 13 April 2021

Saleem Samad is an independent journalist, media rights defender, and recipient of Ashoka Fellowship and Hellman-Hammett Award. He could be reached at saleemsamad@hotmail.com; Twitter @saleemsamad